Once I’ve created a digital photographic and scanned record of an old photo album, the next step for me is usually to provide accompanying documentation of the images. This record will provide an underlying reference system to the research which follows. In my experience, it is all too easy to seize on a name written on the back of one of the photographs and away I go. The risk is that I will often get carried away by the excitement of ongoing discoveries, and this important part of the process will fall by the wayside.

I prefer, therefore, to at least start in as methodical a fashion as I can. That way, I hope to reduce the chance of ending up with a mountain of discoveries, with no easy way to sort out the relevant from the spurious.

From a genealogical and socio-historical point of view, I feel that it’s also very important to consider the nature of the photographic collection within the album as an entity with a complex internal structure. Unless the album has been collated by a photo enthusiast from a variety of non-family sources – and this possibility should always be carefully considered – then the subjects of the photographs will probably have some meaning to the album’s one or more former owners. The people depicted won’t necessarily all be genealogically related to the original owner, but the owner will usually have had some kind of relationship with them. In all likelihood, there will also be relationships between subjects. Indeed, part of the purpose of researching an album – at least for me - is to elucidate such relationships, where they exist, in order to build up a framework on which one can drape the stories of their lives. I will discuss these aspects further in due course, but wanted to emphasize why I stress the importance of thorough documentation at an early stage.

My methods of documentation have evolved somewhat over time, and indeed are still undergoing periodic modification, so I don’t claim that what I describe here is in any way perfect, or that the approach I use will be suited to every reader. I hope to at least provide some ideas that each may use to establish their own best practice.

Provenance

The origin of a photograph album is very important, particularly if it has few – or no - annotations, as it may provide vital clues to the identities of the portrait subjects. We are all familiar with stories of how photographs have survived the generations, but have lost all accompanying identification information and context. It is often a similar story for entire albums and even miscellaneous groups of photographs. I strongly recommend, therefore, that a special effort is made to document the known history of the album – or Aunt Betty’s shoe box full of loose prints - as far as the researcher is able.

This might merely take the form of a sentence or two, such as:

I, Joe Bloggs, found this photograph album amongst the possessions of my great-aunt (my paternal grandfather’s younger sister) , Julia Bloggs (1892-1971), after she died. Nobody else in my father’s family knew anything about the album or the people in the photographs.

or it could be far more elaborate, depending on how much can be discovered. The important thing is that one should aim to preserve all of what is known in as objective manner as possible, making it clear what is established fact and what is conjecture, for any future generations.

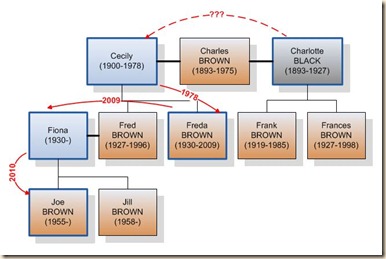

If the album has passed through several hands, as is often the case, then an outline family tree may be useful to illustrate such a history. In the fabricated example shown above:

I, Joe Brown, was given this album in 2010 by my mother Fiona Brown. She and my father had inherited it from his sister (my paternal aunt) Freda Brown a year earlier. My parents had discussed the album over the years with Freda, as it had been passed on to them when Fred & Freda’s parents had died in the late 1970s. My father thinks he remembers being told by his sister Freda that the album used to belong to their father’s first wife Charlotte Brown née Black.

With the particular album that I am currently researching, the donor Jack Armstrong tells me that he bought it at a yard sale in West Chester, Pennsylvania some time in the late 1990s. At the time, the vendors were unable to provide any information as to its provenance. Originally, it had the title “Album” in silver-coloured tin plate letters on the cover, but that subsequently became detached and lost. The fact that the album was “rescued” in West Chester may be irrelevant, as the previous owner could conceivably have purchased it anywhere.

Photograph Index

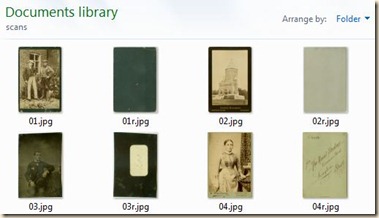

The next task is to compile an index which will eventually contain a summary of the important information about each photograph. I use it for reference and analytical purposes, and often keep a print out in the front of the album. I have used MS Word to create the index, but nowadays I find MS Excel more convenient. It doesn’t really matter what format is used, but one that is easily shared is preferable. My index will contain some the following fields. I’ve highlighted the ones I always include. The remainder I may or may not use, depending on the particular project, and can be regarded as optional. Other researchers may also wish to use other fields that I’ve not mentioned.

Reference – the file name/number given to the scanned/edited image

Format– The photograph type or format e.g. cabinet card, ferrotype, carte de visite, post card, loose print, etc.

Size – Width and height/length of both the card mount and photographic print, in millimetres, measured with an ordinary ruler. By convention, the horizontal dimension is given first, whether this is smaller or greater than the vertical dimension. Alternatively, you can use the measuring tools within Adobe Photoshop (or other image editing software) to determine the dimensions.

Card thickness – The thickness of the card mount is only practical to measure if you have the necessary equipment, such as a micrometer screw gauge, and is probably worth doing only for very detailed studies, e.g. of a particular studio.

Portrait style – e.g. full length/half-length/head-and-shoulders, seated/standing, couple/group, vignetted, etc.

Setting – e.g. studio, outdoors, garden

Photographer – the name of the photographer and/or studio, as printed, stamped, written or embossed on the photo or card mount

Studio Address – the address of the photographic studio, as displayed on the card mount, including the county/state/province/country (Chapman codes in the UK, Country Codes as used by the NZSG) in separate columns

Subject – a brief description of the subject or subjects, e.g. woman and child, or elderly man in top hat

Age(s) – estimated ages of subject(s), using a range to indicate uncertainty, e.g. 3-4 years, or aged 60-70 yrs, etc.

Date – estimated date that the portrait or photograph was taken, again using a range to indicate uncertainty, e.g. 1885-1895, or 1880s

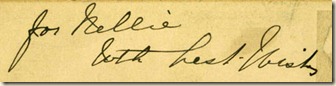

Annotations – full transcripts of any annotations on the card mounts, or on the album pages where the photographs were, including negative numbers

Remarks/Notes – Any other remarks about the photograph, subjects or studio background worthy of note, including possible interpretations by the researcher

Some tailoring of the photograph index will usually be necessary for the researcher’s specific purposes. However, any design should be carefully thought out, with consideration being given to the information which will be required, not only for the analysis of the album contents, but also for the proper citation of photographs.

Citation of Photographs

The citation styles for photographic images, of which there are several, are usually designed to cater for other works of art as well, and are therefore rather generalised. The popular ones (MLA, Chicago, Harvard, APA) follow similar lines, and contain the same essential elements, which are:

- Name of Creator and role, e.g.

- Title or Description of Image

- Year of Composition

- Medium

- Current Location e.g. Name of institution where currently held, Private Collection of [name], etc.

and if the image is reproduced in another work, such as a book, the following additional elements are used:

- Title of Publication

- Author or Editor of Publication

- Location & Name of Publisher

- Date of Publication

- Page number

or on a web site:

- Online Database Name or Web Site

- URL

- Date Accessed

The APA style for works of art in general is given as follows

Artist (last name, first name), artist’s role (in parentheses i.e. Artist, Architect), title, the work type, in brackets [Painting, Cathedral, Chair], country of origin or city, and state, and repository.

Adapting this specifically for photographs, one might therefore produce the following citation:

Pifer & Becker Photo-Palace (Photographic Studio) (estd. c.1887-1895) Portrait of a young man [Photograph], 94-100 Wilshire Building, Superior St, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A., Personal collection of Brett Payne, Tauranga, New Zealand.

The excellent NLM Style Guide provides a detailed description of how to cite photographs, which includes additional elements such as the size of the photograph, and makes the following important suggestion:

Prints and photographs often contain little information to use in constructing a citation. A formal title may be absent and publishing facts unclear. Therefore, include in a citation, whenever, possible the name of a library or other public archive where the item may be found, along with any order or catalog number available.

So I would suggest that the following additional elements should therefore also be considered for inclusion:

- Size of Photograph and Mount or Frame

- Collection Catalogue or Reference Number

There is a large variety of reference management software available, but it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss them in any detail. Wikipedia has a good comparative study summary here. I only have limited experience of a couple, specifically the MS Word add-on EndNote (at $300 very expensive, unless you can get a student discount) and the Firefox/MS Word add-on Zotero (a free download).

I would strongly recommend that those who reference photographs (or any other sources, for that matter) regularly in the course of their writing investigate the use of reference management software. As a “mature student” who has recently returned to academic life after an interlude of 25 years, I was astounded at how simple it makes life when writing up any research that requires formal referencing. I haven’t yet set up my EndNote styles to include photographs, but intend to do so for this album project, and will cover that in a separate article at some stage.

Prints of Photographs

Scanned images are very useful for examination of photographic detail, and have the advantage that they may be handled repeatedly without fear of causing damage to the originals which have been stored safely back in the album. However, nothing beats having actual photographs to shuffle around the table while one is researching timelines, or assessing whether the subject of one portrait is an older version of the subject of another.

Having proper prints made of dozens (if not more) of images can be a costly exercise, and I use a far simpler and cheaper, if somewhat rough and ready, method. I simply print them out on ordinary paper using the very basic Windows Photo Viewer/Print function and a black-and-white Laser printer. Choose the “9x13” print option for cabinet cards (resulting in four images to a page) and the “wallet” option for CDVs or tintypes (nine/page), and they will be very roughly the right size.

I then cut out the prints, leaving margins to write reference numbers and date estimates. Granted, it’s not quite the same as using the originals, but I have the satisfaction of knowing that the originals are safe, and I have reasonable facsimiles to annotate and play around with, at a fraction of the cost of having photographic prints made.

References

Quick Guide to Citing Images, Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar

Citing Images, University of Cincinnati Libraries

Walli, Gaylin (n.d.) How to Cite a Photograph, eHow.com

How to Cite Electronic Sources, The Library of Congress

Citing Medicine: The NLM Style Guide for Authors, Editors, and Publishers, U.S. National Library of Medicine

Comparison of Reference Management Software, Wikipedia